The classic game

The classic game

We already considered a guessing game on this blog, in which Alice asks queries of the form “is the number in this set” and receives yes/no answers.

In this post, we will play a restricted version of the popular game Mastermind. In Mastermind Carole thinks of a secret string of four coloured pins. Alice can query strings and learns the number of matching pins (differentiated between the pins that are correct and in the correct position and the pins that are merely contained in the secret string).

Mastermind has been extensively studied in combinatorics. Already in ’77 Knuth showed that Alice can always win in at most 5 moves. Here we want to find asymptotics for the game when Carole chooses a string of length .

To make things easier for our calculation, we will restrict the game to binary strings. Also, Alice only learns the Hamming distance (that is the number of differences) between her string and Carole’s string. Alice is computationally unbounded, the only important metric is the number of queries she needs to guess Carole’s string.

The naive algorithm is testing each bit of Carole’s string sequentially, by querying strings of the form 0000, 1000, 0100, etc. This takes queries for bitstrings of length – essentially we do a binary search for Carole’s string. However the algorithm doesn’t seem to be very efficient, it appears that Mastermind is easier than the yes/no game. After all we get much more information with each query.

Can we find Carole’s string with less than queries?

It turns out that it is possible to gather enough information quickly. Disappointingly the strategy is not very useful if we take the computation time into account that Alice needs to produce the secret string.

In Knuth’s algorithm, Alice always queries the string that eliminates the largest number of possible secret strings. This is straightforward to implement by using a brute force approach (we’re computationally unbounded), however the analysis becomes tricky.

Luckily Alice has a very simple randomized strategy that succeeds with high probability. Without thinking she queries random strings and stores the string and its Hamming distance to the secret string. Intuitively a random string is not much worse at eliminating possible solutions than the optimal string.

We have collected enough information when there is only one possible solution left. Let the the secret string be , and let the query string be . Let us try to find the probability that a fixed impostor-string is not excluded by querying , i. e. and have the same Hamming distance from .

The same distance

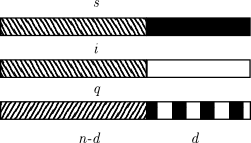

Suppose and differ in positions. How many query strings are there that don’t discern between the two? For to have the same distance from both, only the positions matter where and disagree – where they agree the bits of contribute the same thing to the Hamming distance. So positions of are completely arbitrary. In the remaining positions we need to make sure half the bits agree with and the other half agrees with . Clearly this is only possible if is even. Already after the first query we’ve excluded all impostors that have an odd distance from . Pretty neat.

For even we get $$\mbox{Pr}[i \mbox{ survives}] = \frac{\left({{d}\atop{d/2}}\right) \cdot 2^{n-d}}{2^{n}} = \left({{d}\atop{d/2}}\right) \cdot 2^{-d}.$$ Using Stirling’s approximation on the factorials it is straightforward to show that this is essentially

We want to show that after a sufficiently large number of samples , the probability that there is an impostor string left tends to zero. By a simple union bound it suffices to show $$ \sum_d \left({{n}\atop{d}}\right) \cdot \left(\frac{2}{\pi d}\right)^{t/2} \rightarrow 0.$$

Let’s try to bound the individual summands. We do a case distinction. First consider the case where . By Stirling’s formula we can bound $$\left({{n}\atop{d}}\right) \leq \left(\frac{en}{d}\right)^d,$$ and thus the summands are no larger than By plugging in the extreme values, 2 and , for and setting we get for sufficiently large and thus the exponent can be bounded from above by .

Hopefully we can also derive such a bound in the case where . In this case we bound the binomial coefficient rather crudely by . Then the summands are not larger than Bounding by and setting we get $$\frac{2n}{t} - \log {\pi d}{2} & \leq \frac{\log n}{2} - \log (n/(\log n)^3) \ = \frac{\log n}{2} - \log n + 3 \log \log n \ = 3 \log \log n - \frac{\log n}{2}. $$ Again this is smaller than for sufficiently large and we can bound the summands by in this case too.

Now we can easily bound the whole sum for $$ \sum_{d} \left({{n}\atop{d}}\right) \cdot \left(\frac{2}{\pi d}\right)^{t/2} \leq \sum_d 2^{-3t/4} \ = n2^{-3t/4},\ $$ and this goes to zero rather quickly.

Hence a sublinear number of queries suffices to narrow down the solution space to a single candidate. An information theoretic argument shows that this is optimal. We get bits in every query and the secret string has bits, proof by handwave.

We’ve shown that after queries we’ve collected enough information to exclude all but one possible solutions. We can then find the remaining solution by brute force. Unfortunately we can’t improve much on that method: Checking whether there is a valid solution given queries and answers is NP-complete.

Optimizing functions (like the Hamming distance from a fixed string) using only the answers from an oracle is studied under the name “Blackbox Complexity”. The applications are mainly in the analysis of evolutionary and genetic algorithms. In theory algorithms base their decisions solely on the evaluation of a problem specific fitness function. Blackbox complexity tries to prove lower and upper bounds or the running time of these algorithms for different function classes. Currently only very simple functions are tractable mathematically.

The analysis of Mastermind I presented here is from a FOGA ’11 paper by Doerr et al. A slightly different take on the problem that some might find easier to follow can be found in Anil and Wiegand “Black-box Search by Elimination of Fitness Functions”.