Hashing is a popular way to implement associative arrays. The general idea is to use one or more hash functions to map a very large universe of items down to a more compact set of positions in an array , the so called hash table. Typically one assumes that the hash function is picked randomly and distributes the items uniformly among the possible positions. In practice this is of course not the case as such a function would have enormous storage requirements, however one can get close enough to make the assumption valid.

As one inserts more and more items in the hash table, it becomes increasingly more probable that two items are mapped to the same position–a collision occurs. There are many different strategies to deal with this problem. The simplest is probably chaining where one stores a list of items at every position. This clearly yields constant worst case insertion time. For retrieval, the correct list is found by a hash calculation followed by a linear search through the list to return the correct item. It is very easy to show that the lists are of constant length in expectation, as long as the occupancy ratio of the hash table, i. e. the ratio items/positions, remains bounded. A balls-into-bins argument and a little more calculation shows1 that the expected worst case retrieval time is .

Hashing with chaining is already pretty efficient and very easy to implement, making it quite popular. For example the OpenJDK Hashtable implementation uses this method.

In this post we will explore the performance of a relatively recent2 variation of hashing called cuckoo hashing. Here one uses two independent hash functions to give every item two possible positions. For retrieval we simply check both locations, so the worst case retrieval time is improved to a constant. This can even be done in parallel.

The name cuckoo hashing stems from the way we deal with collisions. If the first position is already occupied, the old item is kicked out, very much like the nestmates of young cuckoos, and tries settling at its alternative position. If that is also occupied, the current item is again kicked out. This process repeats until one item finds a free position.

It is not clear that this procedure always terminates, or, if it does, how long it takes. We will find a bound on the maximal occupancy of the table that still guarantees termination.

Before we look at the performance of the greedy insertion algorithm that I outlined above, let us first try to find an easy bound on the maximal occupancy.

Consider the bipartite graph of items on the left and hash table positions on the right. Every item has two possible positions to which can be assigned. Clearly a successful insertion of all items is equivalent to computing a left-perfect matching in this graph. If there is no such matching, the greedy algorithm can’t terminate.

A simple necessary condition for the existence of a matching is that for any subset of items we have a sufficient number of positions available. A famous result, the “Marriage Theorem” by Hall in 1935, shows this condition to be sufficient too.

A different way to look at this is to consider the graph in which table positions are vertices and there is an edge between two vertices when we need to insert an item that maps to them. Usually this graph is called the cuckoo graph. We seek a matching of edges to vertices. By Hall’s theorem it exists if and only if there is no subgraph that has more edges than vertices.

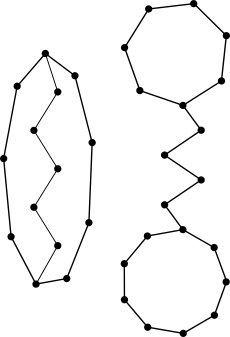

These graphs are too dense.

We want to use the first moment method to find a bound for the appearance of such subgraphs. Hence we have to calculate their expected number. There are many graphs with more edges than vertices, too many to tackle the expectation with our limited knowledge of probability theory. Luckily we can make a clever observation. If there are no subgraphs with more edges than vertices, there can’t be subgraphs with exactly one more edge than vertices.

There are only two types of these graphs, see the figure to the right. Both can be characterized by three numbers. Either the length of the three paths, or the size of the two cycles and the length of the connecting path. As all of these numbers must be smaller than , there can be at most a cubic number of forbidden subgraphs. If we simplify the problem a little3 and consider the graph to be a , a random graph on vertices where every edge is present with probability , a fixed subgraph with edges is contained with probability . Hence the probability that a fixed forbidden graph appears is certainly smaller than .

As we have at most forbidden subgraphs, the expected number is at most . This value goes to zero for and thus (modulo our simplified graph model) for graphs with less than edges. Therefore in such graphs no forbidden subgraphs occur with high probability and insertion can work in principle.

But how about our greedy algorithm, is it sufficient for inserting new elements? Let’s consider a directed version of the cuckoo graph. Every edge is directed towards the position where the element is moved to in case it gets kicked out of its current spot. Hence elements reside at the edges tails and every node has at most one outgoing edge. Inserting a new element corresponds to inserting a new edge and directing it. If both endpoints already have an outgoing edge, we select an arbitrary one and kick the element out of its position. This means we reverse the edge and check at the new position whether there is already an outgoing edge.

This process fails if we cross an edge for the third time. The first time we see it, we flip it and continue. If we see it again, there was a directed cycle somewhere further down the path, that made us return. Note that this cycle still exists, only it now has the opposite direction. If we see the edge a third time, there was also a directed cycle on the other side–the process loops forever between these cycles.

This took way longer to make than I expected.

But we’ve shown that these types of subgraphs don’t appear with high probability! Hence the greedy routine works for hash tables with an occupancy of less than 0.5.

In another post we might explore how long it takes in the worst case to find a free spot (not long) and how many collisions we have in expectation (a lot fewer than with just one hash function).

Practitioners are probably not particularly thrilled to have a hash map that uses twice the amount of storage necessary even if offers constant retrieval time. Here a simple generalization of the method provides a dramatic improvement. If instead of taking two hash functions we use more, the occupancy threshold increases rapidly. Already for three functions we achieve more than 90% space utilization.4 However the math needed to prove that is much harder because we have to deal with hypergraphs. With more hash functions the number of collisions also decreases, though not a sharply as when going from one to two functions and retrieval can still be done very quickly in parallel.

A C implementation of d-ary cuckoo hashing can be found here.

Original paper Pagh et. al. 2001↩

This is a simplification, because we would have to use a random graph model where we fix the number of edges to the number items. For our purposes these two models are similar enough.↩